On May 10, 2006, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement2 (IRSSA) was signed in Canada. The event was heralded as the beginning of a new chapter in Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Inuit, Innu and Métis). It was seen as more than an acknowledgement of the truth about atrocities committed against Aboriginal children in the Indian Residential Schools (IRS) system. It was seen as the first step towards reconciliation between Canada and its Indigenous Peoples. The IRSSA was implemented on September 19, 2007.

Included within the IRSSA was schedule “N”, the mandate for a truth and reconciliation commission. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), considered to be the cornerstone of the IRSSA, began its work on June 1, 2008. Overall goals of the TRC focus on promoting healing, educating, listening, and the preparation of a report for all parties that includes recommendations for the Government of Canada regarding the IRS system, experience and legacy.

On June 11, 2008, Canada’s Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Stephen Harper, publically apologized to Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples for the IRS system, admitting that residential schools were part of a Canadian policy on forced Aboriginal assimilation. Prime Minister Harper and the leaders of every major federal political party in Canada publically decreed there was no place left in Canada for the policy of forced Aboriginal assimilation.

In December of 2015, the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was released and Canada’s Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, declared Canada would implement the 96 calls to action included in the report.

Nothing has significantly changed since the IRRSA was signed and the apology given: The Inuit in Nunavut are still without food, First Nation women are still missing, Indigenous suicide rates and life expectancies have not changed, there is no Indigenous education system, the gap in wealth between Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous communities has not narrowed, etc.; and, unfortunately, nothing will change. There is simply no mechanism in place that will result in the change needed to solve these and other problems facing Canada’s native people; problems created by the IRS system and the policy of forced assimilation.

Reconciliation is the act of reconciling where, in this instance, to reconcile is to restore, repair or make good again to achieve a settlement. The TRC’s mandate was about revealing the IRS system for what it was. It was not about restoration. Indigenous people in Canada still need to have their lives restored to achieve settlement. They need to be given back tools taken from them through which solutions can be built. These tools are traditional Indigenous infrastructures, infrastructures that were destroyed by the IRS system and forced assimilation. Canada’s Indigenous Peoples need to have their traditional infrastructures restored and repaired to achieve settlement and permanently solve problems facing their communities.

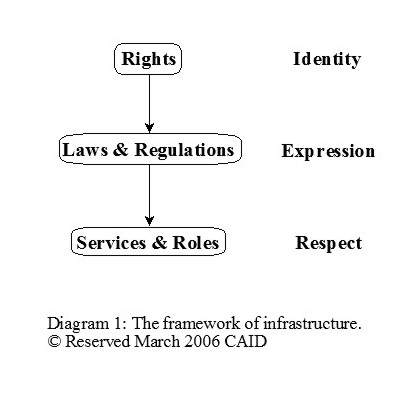

Infrastructure is the basic underlying framework of an organization. On a national level, it is the framework of rights, laws, regulations, services, and roles that are essential in building a program to respond to a citizen’s need (Diagram 1). Rights provide the foundation for a nation’s identity. The expression of rights defines the identity of the nation to whom the infrastructure belongs. This national identity is visibly expressed as the moral fabric of a nation within the aggregate of its laws and regulations. Services and roles that respect the law and regulations of a nation therefore respect rights of citizens within that nation. Therein lies the foundational problem in Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous People.

Non-Indigenous people built Canadian law and regulations purposely excluding Indigenous rights. Because of this, the identity of Canada’s Indigenous people is not part of Canada’s national fabric and so, Canadian law and regulation do not allow the expression (protection) of Indigenous rights. Canada’s policies, legislation, services and programs therefore do not recognize, and are antagonistic to, Indigenous rights to self-determination, self-governance, manage traditional lands, and develop distinct economies based on traditional pursuits and their resources. The dysfunctional legacy from Canada’s refusal to protect Indigenous rights is the absence of functioning traditional Indigenous infrastructure; including infrastructures for, trade and commerce, education, resource management, traditional foods, health, justice and more.

In 1982, when Indigenous and Treaty rights were included into the Constitution Act, Canada created a dichotomy that, if left unresolved, will lead to the separation of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples and destroy Canada. Canada recognized Indigenous rights without an infrastructure through which they could be expressed and respected, placing Indigenous and non-Indigenous people on a collision course. There are only two paths now available to Canada:

1- Canada can refuse to change, preventing further infiltration of Indigenous rights into Canadian infrastructure. However, this path will violate the Constitution Act (1982) and international laws on the rights of Indigenous People3 and Genocide4. The ultimate result of this choice will be the division of Canada into Indigenous and non-Indigenous states.

2- Canada can change, respectfully harmonizing Indigenous rights and identities into Canadian infrastructure. This can be done by obtaining definition for Indigenous law and regulation through meaningful consultation. The ultimate result of this path will be the restoration of Indigenous rights, respect, and missing traditional infrastructure; the reconciliation of Canada with its First Peoples.

All of Canada’s infrastructures have been built without the inclusion of Indigenous rights. Now that Aboriginal rights have been recognized by Canadian legislation within the constitution, Canada’s infrastructure must change or Canada must enforce its policy of forced assimilation and continue living a lie. In words from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People5,

“A country cannot be built on a living lie. We know now, if the original settlers did not, that this country was not terra nullius at the time of contact and that the newcomers did not ‘discover’ it in any meaningful sense. We know also that the peoples who lived here had their own systems of law and governance, their own customs, languages and cultures. They were not untutored and ignorant; they were simply cast by the Creator in a different mould, one beyond the experience and comprehension of the new arrivals. They had a different view of the world and their place in it and a different set of norms and values to live by.”

The means to reconciliation is through the rebuilding of destroyed traditional Indigenous infrastructures. Infrastructure is rebuilt by harmonizing Indigenous rights and identities with Canadian infrastructure to create respectful infrastructures that honour and protect both Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights.

Detailed national infrastructures do not exist until citizens have a need that must be met. Indigenous Peoples in Canada are in need and have been for decades. The reason their needs have not been met is because Indigenous rights have been withheld by Canada’s assimilation policy.

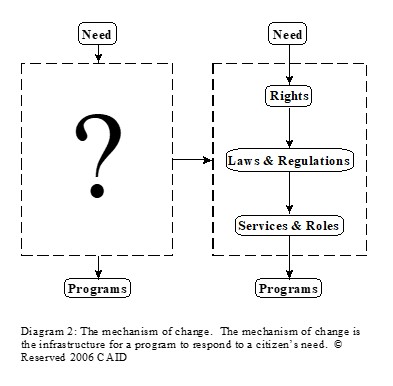

When citizens have a need, it must be translated into a functional program capable of providing the solution to that need. The process happening between the need and the functioning program is the mechanism of change. The finished mechanism of change for a nation’s need is the infrastructure for the program providing the solution (Diagram 2).

A valid national need is supported by rights. Rights are inherent, contractual or legislated. Rights supporting a valid national need are expressed in law and interpreted by regulation. Regulations provide the blueprint for supporting services that are supplied by various governmental and non-governmental agencies, each playing their own role in the final solution. In national infrastructure, a functioning program supplies the final solution. The national infrastructure for a solution includes rights, law and regulations, and services and roles. Programs are not infrastructure. They are solutions created from functioning infrastructure.

Aboriginal rights were recognized by Canada in 1982, yet there has been no advancement of these rights through the mechanism of change. Canada has prevented the progression of Indigenous rights into law and regulations by enforcing non-Indigenous law and regulations that antagonistically suppress Indigenous rights. The most appropriate example of this is with the Indigenous right to hunt for livelihood in Ontario. The Constitution Act and Treaties signed with Ontario’s First Nations guarantee the right to hunt for livelihood but the provincial government has legislated against commercial wildlife harvest, enforcing this law against First Nations. Further, Ontario withholds economic development funds for traditional First Nation wildlife-based economic development and meaningful Indigenous consultation on wildlife management while managing wildlife populations6 by retailing hunting rights to non-Indigenous recreational hunters. The Province of Ontario is not an isolated example.

With Aboriginal rights guaranteed by the Constitution Act, the next step in the mechanism of change is to have Aboriginal rights expressed into law and interpreted by regulation. [Again, it remains to be seen if Aboriginal rights are the same as Indigenous rights.] This is accomplished with a national Elder consultation process1.

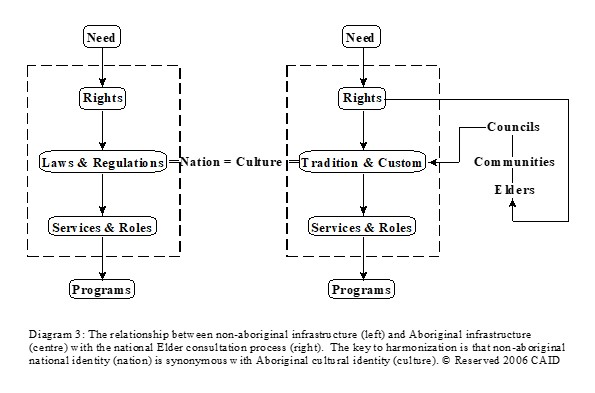

For simplicity, a nation is a body of people sharing a common culture. A nation can also be functionally defined by its laws and regulations (Nation = Law + Regulations). Culture is defined by its tradition and customs (Culture = Tradition + Customs). However, traditions are laws and customs are regulations. In this context, again for simplicity, Nation = Culture. This may seem like semantics but these simple equations provide the key to defining Indigenous law and regulation for rebuilding missing infrastructure (Diagram 3).

Indigenous tradition (oral law) is carried by Elders and Indigenous customs (regulations) are carried within the Indigenous nation by those parts of the nation whose roles are to manage traditional law (councils). To capture Indigenous law and regulation as a blueprint for a missing infrastructure, temporal interpretations of oral law must be spoken on rights by Elders and then brought through the Indigenous nation in consultation format; Elders, communities and the nation’s institutions (councils)1. As the results of the Elder consultation spread through the nation, the regulation framework of a missing traditional infrastructure gains definition. This national Elder consultation process provides the nation’s traditional law and regulations to rebuild missing infrastructure services and roles.

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have multiple missing infrastructures and will need to be consulted in a nation-by-nation manner with nation-defined national Elder consultation processes.

As mentioned earlier, national infrastructure does not exist until a citizen has a need that must be met. We can recognize Indigenous rights and undertake a national Elder consultation process to express rights into law and define regulation for a given infrastructure. However, infrastructure services and roles are tailored to meet a need. They can not be rebuilt until the nation has a need for them. A pilot project is needed to build the services and roles step in the mechanism of change.

The pilot project is a specific focused need that has a high profile and whose resolution would have a significant impact on the Indigenous nation involved in rebuilding its infrastructures. It is the high profile nature and final impact of the pilot project that provides both the driving force for everyone to work diligently and the yardstick to measure the new infrastructure’s success in providing the solution to the pilot project’s need. An example of a focused pilot project would be the building of a traditional food infrastructure for the Inuit of Nunavut to provide affordable food and reverse the region’s trend towards starvation.

Regardless of which Indigenous nation a pilot project occurs within, it will create an infrastructure framework. This framework can be used as an adaptable base to more quickly build similar missing infrastructures within other Indigenous nations. Each of the other nations will still need to undergo a national Elder consultation process to fine tune the framework for their own laws and regulations.

As an example: In February 2008 the Government of Canada announced it would spend $70 million over two years on its objective to establish a new framework for Indigenous economic development. Given an understanding of the mechanism of change and the ability of a pilot project to create an infrastructure framework, a pilot program could have been initiated in one nation and the generated infrastructure framework could have been used as a starting base for the rest of the country. An economic development infrastructure pilot program in Treaty #3 would have cost approximately $5 million leaving $65 million for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to harmonize the Treaty #3 framework infrastructure with Canadian infrastructure and to fund national Elder consultation processes in other Indigenous nations to fine tune the framework for their laws and regulations. Please note though, economic development is an infrastructure built on other supporting core infrastructures. These supporting core infrastructures would have to be built before or at the same time as building an economic development infrastructure framework or there would be no new “functioning” programs created.

Indigenous and non-Indigenous infrastructure can not exist separately in Canada. This is a dichotomy that leads to permanent division of the country. Indigenous and non-Indigenous infrastructures must harmonize to provide the blended infrastructure able to provide programs with solutions that respect both cultures. At this point in our mechanism of change we have Aboriginal rights guaranteed by the Constitution Act, Indigenous law and regulations from the Elder consultation process, and we have defined blueprints for Indigenous services and roles. In essence, we have the Indigenous infrastructure we are rebuilding written on paper.

The harmonization process is simple. Each level of the infrastructure must be harmonized between the Indigenous infrastructure and existing non-Indigenous infrastructure; rights to rights, law to law, etc. We must ensure there are no conflicts at each level of the infrastructure. Identified conflicts must be resolved at this point in infrastructure rebuilding, before the pilot project is implemented.

Virtually all conflict will arise from Embedded Forced Assimilation Barriers (EFABs). EFABs are laws, regulations, services, roles, or programs that were designed under the auspices of Canada’s policy on Aboriginal displacement and forced assimilation. Their purpose was to block Indigenous rights from being realized while removing existing rights to lands and resources. In essence, EFABs are tools used to destroy and withhold traditional Indigenous infrastructure in Canada. The Prime Minister of Canada, and every major Canadian political leader, may have stood in front of the world to decree that Canada has no place for a policy on forced Aboriginal assimilation, however, not one Canadian infrastructure has been screened to remove its EFABs. Forced Aboriginal assimilation, and its ensuing cultural genocide, is very much alive in Canada until the infrastructure harmonization process identifies and removes EFABs.

5. Pilot Project Implementation:

The pilot project should be implemented as soon as its infrastructure finishes the harmonization process. The implementation of the pilot project will:

- Identify unforseen obstacles as early as possible in the dissemination process; and,

- Validate the correct functioning of the infrastructure by producing the program(s) needed to solve the high profile conflict in the Indigenous nation chosen for the pilot project.

6. Pilot Project Dissemination:

At this point in infrastructure rebuilding, the missing Indigenous infrastructure has been defined and harmonized with non-Indigenous infrastructure. This gives us the general infrastructure framework of rights, law, regulation, services and roles to bring to the rest of Canada’s Indigenous nations.

The general infrastructure framework must be disseminated to each Indigenous nation in Canada to fine tune it through nation-specific national Elder consultation processes. These fine tuned infrastructures must again pass through the harmonization process. When harmonized, the new Canada-wide Indigenous infrastructure is ready to be implemented for nation-specific needs.

The final reconciliation is not so much a step in traditional Indigenous infrastructure rebuilding as a milestone. When each of the missing infrastructures has gone through a pilot project, the general framework adjusted for each nation and these new Indigenous infrastructures implemented, Canada will have reconciled with its Indigenous Peoples.

Phase 1: Pilot Program Development:

To rebuild a missing traditional Indigenous infrastructure we need to initiate the mechanism of change defined earlier. This includes:

- A national Elder consultation process;

- A high profile pilot project whose solution has a significant impact;

- Harmonization of the new infrastructure;

- Implementation of the pilot project;

- Dissemination of the general framework for Elder consultation processes in other nations;

- Additional harmonization; and,

- Final implementation across Canada .

To rebuild all missing traditional infrastructure, we need to bring a high profile pilot project for each of the missing infrastructures through the mechanism of change and then disseminate and implement them across Canada. The core infrastructures that need development are:

- Trade and commerce;

- Traditional Food;

- Resource Management;

- Justice;

- Education;

- Health;

- Governance; and,

- Community.

There will be other non-core missing infrastructures that need rebuilding; ie. economic development. As they arise, they can follow the same rebuilding process building on top of core infrastructures.

Choosing where Phase 1 core pilot infrastructures will be developed depends on the strength of the pilot project. We simply choose the area of Canada with the most conflict or need in each of these missing infrastructure areas. For examples:

- Nunavut, traditional food;

- British Columbia, justice;

- Northwestern Ontario, trade and commerce; and

- Saskatchewan, resource management.

Canada’s Indigenous people are both urban and land based and they are First Nation, Inuit, Innu and Métis. Infrastructure needs to be restored for all of these groups. However, not all of these groups need each of the eight core infrastructures.

Canada’s policy on forced Aboriginal assimilation was given a death sentence on June 11, 2008. We simply need to untangle it from the fabric of Canada. The rebuilding of missing Indigenous infrastructure will remove embedded forced assimilation barriers (EFABs) from Canada’s policies, legislation, regulation, government departments and agencies, and programs. A Canada liberated from its shackles of forced Aboriginal assimilation will be free to grow in new, prosperous directions with its Indigenous partners.

Not everyone in Canada will rejoice at the prospect of joint stewardship with Indigenous People. In general, there will be three groups that will fear change because they perceive they will profit more from maintaining the status quo. These are:

- Select government departments and agencies;

- Resource-based corporations; and,

- Miscellaneous Indigenous groups.

Government departments and agencies involved with control of renewable resources (timber, wildlife, fish, etc.), non-renewable resources (mining, oil, hydro-electricity, etc.), and those managing current infrastructure for Indigenous communities (training, education, health, governance, etc.) will be very afraid of rebuilding traditional infrastructure. They will fear joint decision making processes, addressing Indigenous concerns within the context of joint stewardship, split revenues, and the transfer of services and budgets into rebuilt traditional infrastructure. These departments need to understand that new traditional infrastructure and existing infrastructure will be harmonized to include roles for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. No one will lose.

Resource-based corporations have enjoyed a carte blanc in remote Canada, many times they are heralded as the much needed regional employment resource. Those corporations that have built a relationship with Indigenous communities juxtaposed to their operations, will not be afraid of infrastructure changes. Those that have shown contempt and disrespect for Canada’s Indigenous People will be very afraid of the impending inclusion of traditional Indigenous infrastructure. However, in the end, with whatever changes occur, businesses will adjust and everyone will move forward.

Indigenous communities, governances, organizations, and lobby groups have survived by competing against each other for the insufficient funds offered by federal and provincial authorities. This has created an environment of mistrust where there is too little for too many. Because of this, some Indigenous organizations have come to consolidate their position by controlling information and resources. Unfortunately, what these groups can’t control, they fear and speak against. These organizations need to have their fears about infrastructure rebuilding addressed so everyone can see the process of rebuilding and implementation has enough work for all. As a point in fact, many Indigenous organizations will find themselves in a position where they need to adjust to, or redefine, their broadened role in a restored First Nation. No one will lose.

There are only three types of organizations from which to choose a working group to facilitate and oversee the pilot program development phase of missing Indigenous infrastructure restoration:

- A government organization;

- An Indigenous organization; or,

- A non-governmental organization.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) is the government organization that would prefer to directly or indirectly control work on infrastructure pilot program development. INAC was created as the enforcement agency for Canada’s policies on forced Aboriginal displacement and assimilation. In this regard, INAC has played a central role in destroying traditional Indigenous infrastructure and centralizing non-Indigenous infrastructure supplied to First Nation communities under INAC control. Unfortunately, there has been no fundamental change in INAC’s directives, policies or operations in the period leading up to or following the Prime Minister’s announcement that forced Aboriginal assimilation would no longer have a place in Canada. Because of this, INAC, as an institution, will still function with EFABs even though many individuals within INAC are sincerely dedicated to helping Indigenous people. INAC can not facilitate or oversee the pilot program development phase of Indigenous infrastructure restoration. Nevertheless, INAC has extensive personnel resources and will be involved throughout the entire infrastructure restoration process. INAC will also have a primary role in infrastructure harmonization and Canada-wide implementation of redefined Indigenous infrastructure. [In 2017, the Government of Canada announced it would dissolve INAC and create two new departments, Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. It will be a number of years before it can be ascertained if anything changed with the dissolving of the INAC. We will continue to use ‘INAC’ in this document as we are uncertain which new department would be involved in a pilot project.]

Indigenous organizations are not impartial, many have developed as part of the INAC-controlled Indigenous infrastructure, others have evolved to champion Indigenous rights withheld by INAC and still others have risen to prominence by controlling information and resources. Unfortunately, there are no Indigenous organizations that would be impartial, respected by both Canada and Indigenous nations, have the needed expertise, and who would be without affiliation to either First Nations organizations or the Government of Canada. Still, the entire infrastructure rebuilding process can and should utilize personnel from Indigenous organizations as both core and ancillary staff.

To facilitate the pilot program development phase, a non-governmental organization (NGO) is needed. This NGO should be:

- Respected by both Canada and First Nations (fair);

- Unable to profit from the results of the process (impartial);

- Without affiliation to either First Nations organizations or the Government of Canada (independent);

- Specialized in the process of infrastructure development (knowledgeable);

- Founded on the premises of consultation, education and facilitation (dedicated); and,

- Solely interested in doing quality work regardless of the direction the work takes (honest).

The pilot program development phase of Indigenous infrastructure restoration needs a very specialized not-for-profit, charitable non-governmental organization (NGO) to fulfil these criteria.

When analysing costs, it is customary to consider the cost of maintaining the status quo. However, Canada has recognized Aboriginal rights in the Constitution Act, implemented the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, launched a Truth and Reconciliation commission, publically stood and denounced forced Aboriginal assimilation, and committed to establishing a new framework for Indigenous economic development. The status quo is not an option in Canada.

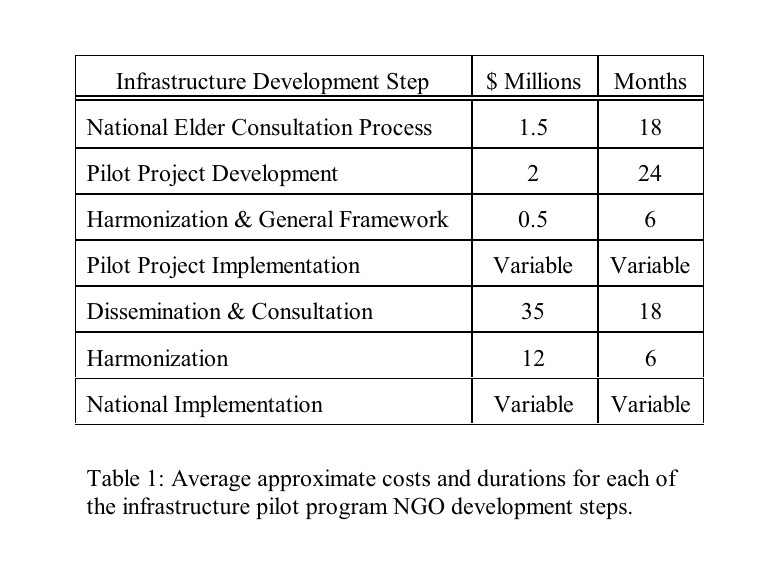

The pilot program development of traditional Indigenous infrastructure can occur with an individual missing infrastructure or proceed en mass with the pilot development of all missing core infrastructure. It should be noted that the development of the justice infrastructure will be twice as costly and take twice the time of other infrastructure developments. Average approximate costs and durations for each of the infrastructure pilot program NGO development steps are found in Table 1. Costs for pilot project implementation would include both professional support and capital costs. Implementation costs can not be approximated without pilot project identification and infrastructure detail.

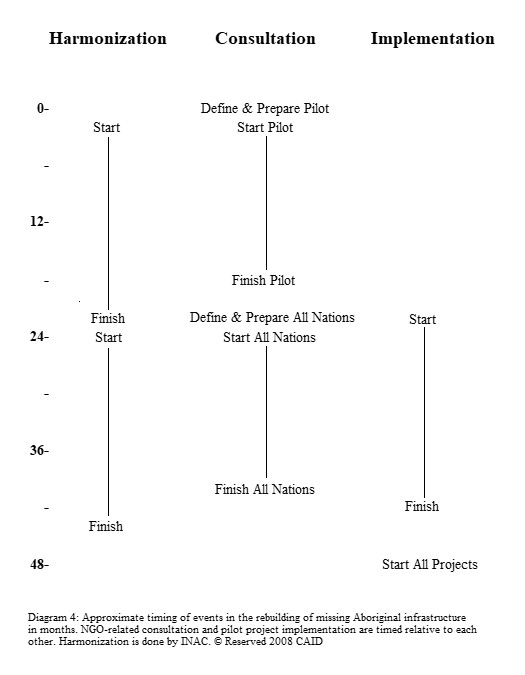

Infrastructure pilot program development steps within each infrastructure’s rebuilding do not necessarily follow in series and some degree of parallel development will occur shortening the time for development (Diagram 4).

It should be noted when the time line of Diagram 4 is extrapolated, Canada’s Indigenous people will have all infrastructure restored and functioning in 6 to 8 years. Assuming Canada chooses change and reconciliation, poverty will be completely eliminated in Indigenous communities within 10 years.

Canada has declared an end to forced Aboriginal assimilation and set an objective to establish a new framework for Indigenous economic development. This objective is focused at ending the horrendous cycle of poverty seen in most Indigenous communities in Canada. This poverty was caused by the purposed destruction of traditional Indigenous infrastructure.

Economic development is an end stage infrastructure supported by core infrastructures such as trade and commerce, resource management, and traditional foods which, in turn, are supported by other core infrastructures such as education, community, health and governance. Any model or process for building a new framework for economic development would have to include the restoration of destroyed core Indigenous infrastructures. When core Indigenous infrastructures are rebuilt, an economic development initiative will be a simple consultation process asking what an Indigenous nation would like to do and then facilitating professional help, training, and other building materials.

Despite apologies and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Canada has no mechanism through which to resolve problems created by the Indian Residential Schools system and the policy of forced assimilation, including poverty. Indigenous people need to be given back their traditional core infrastructures from which, and through which, they can permanently solve problems facing their communities.

Missing Indigenous infrastructure can be rebuilt through a process of meaningful consultation, harmonization, and pilot project development to yield infrastructure frameworks. These initial infrastructure frameworks can be disseminated across Canada for meaningful consultation, harmonization, and implementation. The harmonization of rebuilt Indigenous infrastructure with non-Indigenous infrastructure will remove embedded forced assimilation barriers from within Canada creating a country capable of honouring both cultures.

Canada now has, for the first time, a process through which systematic restoration of traditional Indigenous infrastructures destroyed by forced assimilation can be accomplished. These infrastructures would already exist if Canada had not chosen to displace and assimilate its Indigenous Peoples. When traditional Indigenous infrastructures are rebuilt, reconciliation will be complete. Canada will then move forward in mutual respect and joint stewardship.

1. (2008) Herbert, R. G., A Model to Establish a New Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development in Canada: A Proposal in Response to the Federal Government of Canada Objective to Establish a New Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development in Canada. https://caid.ca/Model031108.pdf

2. (2006) Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. https://caid.ca/IRSSA2006.pdf and https://caid.ca/IRSSASchN2006.pdf

3. (2007) Resolution 61/295. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://caid.ca/UNIndDec010208.pdf

4. (1948) United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Resolution 260 (III) A. https://caid.ca/Genocide1948.pdf

5. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 2: Restructuring the Relationship. Chapter 1, Introduction. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP2.1.pdf

6. (2008) Herbert, R. G., First Nation Rights and Turkey Harvest-Management in Ontario: A Response to the Proposed Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Wild Turkey Management Plan for Ontario, 2007 (EBR Registry #010-2424) and to Proposed Amendments to Regulations Under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act (1997) to Implement a Fall Hunting Season for Wild Turkeys, and Establish Open Seasons for Spring and Fall Hunting of Wild Turkeys in Specific Wildlife Management Units (EBR Registry #010-2429) https://caid.ca/CAIDTur022508.pdf

© Christian Aboriginal Infrastructure Developments

Follow

Follow