National infrastructure is a framework of laws, regulations, services, and roles that are used to create programs in fulfilment of rights; rights are guaranteed by laws, laws define regulations, regulations provide blueprints for services and roles, and services provide programs. Programs created from an infrastructure framework respect rights the infrastructure was created to express. Canadian national infrastructure was created without the recognition of Indigenous rights to express non-Indigenous rights. It is a non-Indigenous infrastructure framework incapable of respecting Indigenous rights in its current state.

In 1982, the Constitution Act recognized and affirmed Aboriginal and Treaty rights. Since that time a number of important events have occurred involving Indigenous rights. They include:

- The last Indian Residential School was closed;

- The United Nations passed the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (1989);

- The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) was released;

- The Government of Canada signed the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (2006);

- The United Nations passed a resolution on the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007);

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission began its work in Canada (2008);

- The Prime Minister of Canada apologized for Indian Residential Schools and the policy of Aboriginal assimilation (2008);

- The release of the United Nations recommendations on the duty to consult (2009);

- The Prime Minister of Canada pledged to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions calls to action (2015);

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its final report and calls to action (2015);

- The Government of Canada dissolved the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada department replacing it by two federal departments, Indigenous Services Canada and Indigenous-Crown Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (2017-19);

- The Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls released its final report and calls for justice (2019); and,

- A myriad of cases that have been processed by the Canadian judicial system to support Aboriginal rights.

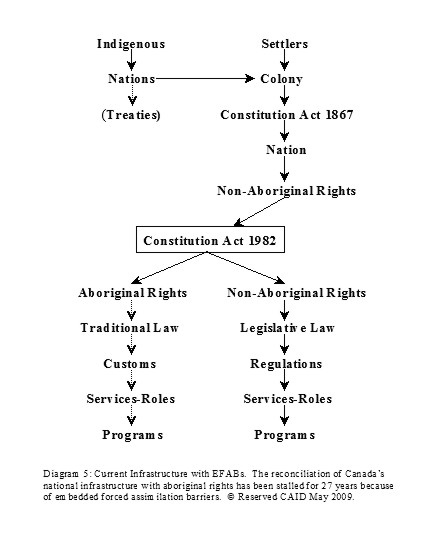

In the 36 years since the Constitution Act recognized and affirmed Aboriginal rights, little has changed for the expression of Indigenous rights in Canada. Aboriginal rights have not been included into Canadian national infrastructure. The Canadian policy of forced Aboriginal assimilation was discontinued in 2008 but secondary policies, legislation and regulations that provided services and programming tools for Aboriginal assimilation still functioned in Canada’s national infrastructure. These are now embedded forced assimilation barriers (EFABs) that block the advancement of Aboriginal rights. As a consequence, Canada’s national infrastructure framework is incapable of recognizing Aboriginal rights unless EFABs are removed.

The Government of Canada announced federal Ministers would review federal legislation, regulations and policies to remove barriers to Aboriginal rights in 2017. In 2018, the Prime Minister of Canada announced a recognition and implementation of rights framework for Indigenous peoples in Canada. However since 1982, it has become clear that Aboriginal rights granted by the Crown under section 35 of the Constitution Act have become an alternate rights regime that denies Indigenous Peoples in Canada their pre-existing sovereignty and Immemorial rights while preventing them from accessing their international right to self-determination.

Canada needs a process that can define Indigenous Immemorial rights and remove EFABs to these rights from national infrastructure. That process must include mechanisms to:

- Accommodate Immemorial rights;

- Provide a new legal basis for a relationship with Indigenous Peoples;

- Reconcile Canada with Indigenous Peoples; and,

- Provide an Indigenous culture database so that all Canadians can understand and respect Indigenous rights.

The process Canada needs to reach these four objectives is Meaningful Consultation. A process for Meaningful Consultation will be described that is able to meet standards set out in Indigenous law, Canadian Common Law, and by the United Nations. The process has four steps:

- Nation Consultation;

- Nation-to-Nation Consultation;

- Harmonization; and,

- Restoration.

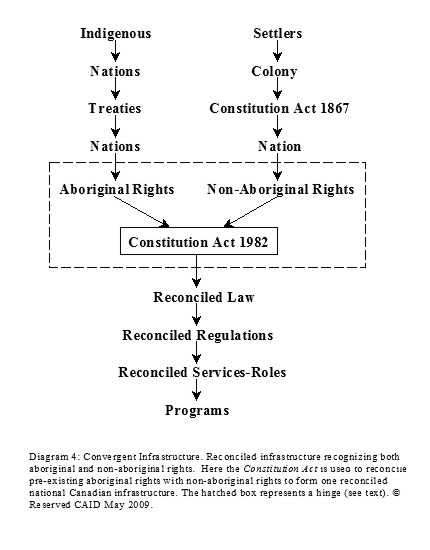

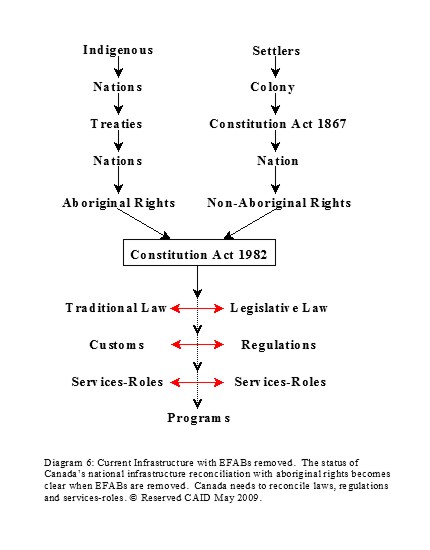

Canada must accommodate Indigenous Immemorial rights in a “reconciled” national infrastructure framework. To accomplish this, Canada must include Indigenous law, regulations and roles into national infrastructure, and, then provide services that allow Indigenous roles to be fulfilled. This is accomplished by first harmonizing culture-based Indigenous infrastructure with existing non-Indigenous Canadian infrastructure and then building parts missing in Indigenous Nations. To reconcile Indigenous infrastructure with non-Indigenous infrastructure, Canada needs a working definition of culture-based Indigenous infrastructure.

Most Indigenous infrastructure was destroyed by Canada’s policy of forced assimilation. However, a diffuse remnant remains in Indigenous Nations with a focal point through Indigenous Elders. Consultation of Elders and Indigenous Nations provides the knowledge and understanding of Indigenous infrastructure needed to generate a working definition for culture-based Indigenous infrastructure. This Nation Consultation process is the first step in Meaningful Consultation. Canada needs the database created by Nation Consultation to fulfill all four Meaningful Consultation objectives. But, the objective to build a database on Indigenous culture is fully satisfied in the Nation Consultation step.

The second step in Meaningful Consultation, Nation-to-Nation Consultation, is a communicative platform between Canada and the Indigenous Nation. It enables Indigenous Nations to provide Canada with detail necessary for Canada to:

- Accommodate Indigenous rights in national infrastructure;

- Create a new legal basis for roles through which an Indigenous Nation will express their rights in a new relationship with Canada; and,

- Reconcile the expression of Immemorial rights by building infrastructure services necessary for Indigenous Nations to function in their new relationship roles.

The Harmonization step removes remnants of the policy of forced assimilation, EFABs, that block the advancement of Indigenous Immemorial rights into a reconciled national infrastructure framework. After EFABs are removed, the final Restoration step can occur.

Indigenous law, regulation and roles must be legislatively placed into Canadian infrastructure and then infrastructure services must be operatively restored into Indigenous Nations to complete the Restoration step. The Restoration step produces reconciled national infrastructure that respects both Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights.

The policy of forced assimilation left most Indigenous Nations with shells of their former institutions. These shells function as non-Indigenous Canadian infrastructure utilizing Canadian law and regulation. Culture-based Indigenous infrastructure roles were lost from these national institutions because Canada purposefully undermined Indigenous law and regulation destroying the expression of these institutional culture-based roles. When Canada undertakes Meaningful Consultation with Indigenous Nations to include Indigenous law, regulation and roles into a reconciled national infrastructure, the pre-existence of Indigenous societal roles will be reconciled with the sovereignty of the Crown.

The Nation Consultation step is a pre-requisite step to all aspects of the Meaningful Consultation process. It is the only part of the process that can be separated and initiated on its own without triggering a full Meaningful Consultation process with an Indigenous Nation. This is because the Nation Consultation utilizes the same work to fulfill a dual mandate to:

- Acquire a database on Indigenous culture; and,

- Define the culture-based framework of infrastructure for an Indigenous right.

It is recommended that Nation Consultations be initiated post-haste and performed by an NGO as part of the general mandate given by the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples to develop a database on Indigenous history and culture6. By using the Royal Commission mandate, political overtones can be removed from initiating Nation Consultations while extending a firm promise for future reconciliation.

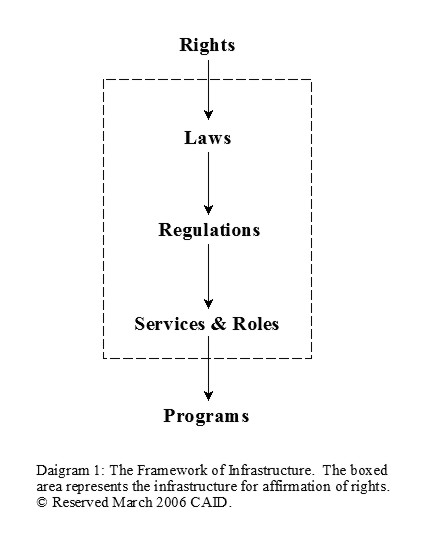

Rights are the foundation of a nation’s identity. Rights are embodied within a nation through an aggregate of its laws and regulation. But, the fulfilled expression of rights only occurs when laws and regulations are utilized to create services whose programs respect rights of the nation’s citizens.

Rights are sovereign truths that cannot be side-stepped. Functional respect for a right comes from a two step process. First, rights must be recognized. To be recognized, rights must be seen and accepted. Second, rights must be affirmed. To be affirmed, they must be supported so they can be exercised. Recognized rights are supported by an infrastructure of laws, regulations, and services. A recognized right is reconciled within a nation, and its culture, through infrastructure. So then, in practical terms Respect = Recognition + Affirmation. Canada cannot respect Indigenous rights if they are not recognized and affirmed into infrastructure.

National infrastructure is the framework of rights, laws, regulations, services, and roles that are fundamental in building programs to protect or express citizens’ rights (Diagram 1). National infrastructure is founded on rights; rights are guaranteed by laws; laws define regulations; regulations define services and roles; and, services and roles provide programs. [Programs are not infrastructure. They are tools created from infrastructure.] Sovereign Indigenous Immemorial rights need to be reconciled through national infrastructure to fulfill their expression and be respected in Canada.

Indigenous Immemorial rights were not included in the 1867 Constitution Act but rights to assimilate Indigenous Peoples and their land were. Canada’s national infrastructure supported this imbalance of rights and created tools such as the residential school system, forced relocation, the Indian Act and wardship to fulfill this expression of non-Indigenous rights. Aboriginal rights have been recognized in Canada for thirty-six years but Canadian national infrastructure (the fabric of Canada) was never altered to reconcile with them. By definition, Canada does not respect sovereign Indigenous rights.

As noted earlier, the Government of Canada announced a reconciliation and implementation of Aboriginal rights framework in 2018. Unfortunately, Aboriginal rights Canada recognized in 1982, and is using in the rights framework, have evolved into an alternate rights regime that denies Indigenous Immemorial rights and blocks access to the international right to self-determination. This happens because alternate Aboriginal rights are being recognized and affirmed within national infrastructure in place of Indigenous Immemorial rights.

Until Canada broadens its definition of Aboriginal rights to include sovereign Immemorial rights and then functionally recognizes them through reconciliation, Canada’s infrastructure will continue to develop programs that are tools for Indigenous displacement and assimilation. Canada must grow as a nation and allow Indigenous Immemorial rights to be expressed. Canada needs to become the nation the 1982 Constitution Act says it is; a nation that respects both Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights.

At first glance, this seems like an overwhelming task. Canada simply needs to begin. Canada is not perfect, but it can be. Meaningful Consultation has the ability to reconcile Indigenous rights with Canadian infrastructure. The goal of Meaningful Consultation under Section 35 is the reconciliation of the preexistence of Indigenous societies with the sovereignty of the Crown7. For reconciliation to occur, barriers (EFABs) to Indigenous rights must be removed and Indigenous Immemorial rights must be included within Canada’s national infrastructure.

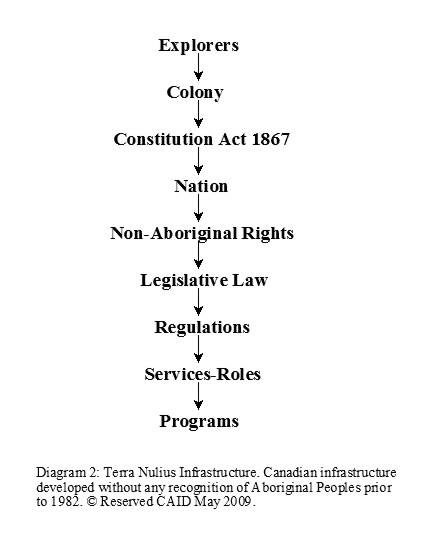

Many legislators and bureaucrats are too close to the system to see the simplistic flow of national infrastructure. The most expeditious manner to gain functional understanding of national infrastructure is strip it down to its most basic form and follow it through Canada’s constitutional history.

Before confederation, the Crown assumed sovereignty over Indigenous lands, resources and peoples through the Doctrine of Discovery. This ensured the land that is now Canada was terra nullius8, unclaimed. After confederation in 1876, and prior to the recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights in Section 35, Canada’s approach to Indigenous Peoples was as if they never existed. The 1867 Constitution Act gave control over Indigenous people and ownership of their land to the federal government. All of Canada became Crown land and Indigenous people became wards of the Crown. The new Dominion of Canada then went on to develop its national Terra Nullius Infrastructure to the complete exclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their rights (Diagram 2).

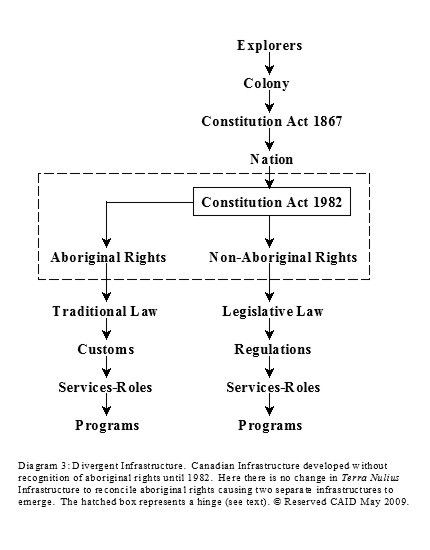

Canada was not terra nullius in any way9, but Canada’s national infrastructure in 1982 was. As a consequence of the Terra Nullius Infrastructure, the only path Indigenous rights could follow when they were recognized and affirmed under Section 35 was to create their own Divergent Infrastructure (Diagram 3). This began to create a dichotomy of rights and infrastructures within Canada; Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples living in the same country with separate, exclusive rights and infrastructures. These two infrastructures, one which excludes Indigenous rights and the other which excludes non-Indigenous rights, must be reconciled to avoid two legislatively separate Canadas. [Ntoe: At first, no one knew that Aboriginal rights in section 35 were not Indigenous Immemorial rights. In fact, they may have been. However, there has been a clear evolution of Aboriginal rights into something that is far less than sovereign Immemorial rights. This move to an alternate rights regime can ultimately be used to close the evolved dichotomy of rights by removing section 35 from the Constitution Act and leaving an Indigenous remnant with no rights.]

The appropriate key to solving the “two Canadas” dichotomy is through the reconciliation of Indigenous Immemorial rights. Were Aboriginal rights created by Section 35 making an exclusive Aboriginal minority in Canada, OR, did Indigenous rights exist before 1982 and Section 35 simply recognize and affirm Indigenous and treaty rights extending from Canada’s original nation-to-nation relationship with its Indigenous Peoples? This dilemma was clearly answered by the Supreme Court of Canada:

“More specifically, what s. 35(1) does is provide the constitutional framework through which the fact that Aboriginals lived on the land in distinctive societies, with their own practices, traditions and cultures, is acknowledged and reconciled with the sovereignty of the Crown. The substantive rights which fall within the provision must be defined in light of this purpose; the Aboriginal rights recognized and affirmed by s. 35(1) must be directed towards the reconciliation of the pre-existence of Aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.”10

Indigenous rights pre-existed the sovereignty of the Crown in Canada and must be reconciled to the Crown. Indigenous rights pre-date the Doctrine of Discovery, the 1867 Constitution Act and the 1982 Constitution Act. If racist assumptions had not prevailed in Canada through the policy of forced assimilation, Canada would have emerged as a nation with a Convergent Infrastructure (Diagram 4) in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights are respected in one “reconciled” infrastructure.

The “one” reconciled infrastructure in diagram 4 does not indicate that culture-based Indigenous infrastructure has no place in reconciled infrastructure. On the contrary, it means that culture-based Indigenous infrastructure and non-Indigenous infrastructure will co-exist, harmonized to work together as national infrastructure capable of respecting the rights of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens.

Federal, provincial and territorial governments have not been able to reconcile Indigenous rights to the sovereignty of the Crown because of EFABs; legislation, regulations, services and roles generated in the Terra Nullius infrastructure from assimilate-by policies that continue to support the defunct policy of forced Aboriginal assimilation. To first step in reconciling Indigenous rights with Canadian infrastructure is that EFABs must be removed to allow the recognition to take place. The second step is functionally reconciling rights within Canadian infrastructure. Meaningful Consultation can remove EFABs and reconcile Canada’s infrastructure to recognize and respect Indigenous Immemorial rights.

The status of Canada’s national infrastructure with EFABs present and with EFABs removed is illustrated in Diagram 5 and Diagram 6 respectively.

Defining Meaningful Consultation:

Canadian courts have established that Meaningful Consultation is an Aboriginal right in Canada guaranteed by Section 35 of the Constitution Act11,12,13,14,15. The goal of Meaningful Consultation is the reconciliation of the pre-existence of Indigenous societies, their Aboriginal rights, with the sovereignty of the Crown7,10. It is important to note that Aboriginal rights in section 35 are defined by the Crown and not by Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples have Indigenous Immemorial rights are based in pre-existing Indigenous sovereignty and rights to manage land, resources and people in their traditional territories to the benefit of their nation.

Aboriginal rights under section 35 were granted by the Crown to fit in with its colonizing objectives. This means that the Crown’s reconciling with a pre-existing Aboriginal right leaves out the rest of the Immemorial right from being recognized and reconciled with. For now though, we are discussing a process for meaningful consultation and that process remains the same for the full Immemorial right or its partial Aboriginal right.

The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) set out four principles to guide the process of renewing the relationship between non-Indigenous and Indigenous rights.16 They are:

- Mutual recognition;

- Mutual respect;

- Sharing; and,

- Mutual responsibility.

1. Criteria for Meaningful Consultation:

Meaningful Consultation is not about turning the clock back for Indigenous Peoples, it is about bringing Canada’s relationship with Indigenous Peoples and their rights forward to where they should have been if forced assimilation had never occurred.

Meaningful Consultation provides a process through which:

- Indigenous rights can be accommodated;

- A new legal basis for Canada’s relationship with Indigenous Peoples can be formulated;

- Reconciliation can occur between Canada and its Indigenous Peoples; and,

- An Indigenous culture database can be prepared for Canada;

Meaningful consultation must be defined by both objective-based criteria and functional criteria. A Meaningful Consultation process that affirms the right to consultation, the goal for reconciliation, Indigenous guiding principles and the Royal Commission’s guiding principles will have the ability to provide:

- Canada with a deep understanding of Indigenous culture and rights;

- Definition for Indigenous law and regulation;

- Framework definition for culture-based Indigenous infrastructure;

- Definition for modern culture-based roles for Indigenous Peoples in Canada;

- Definition for new roles for federal, provincial and territorial governments with Indigenous Peoples;

- Definition for framework on shared land and resource management;

- Definition for a shared destiny in Canada through a legislative base;

- Reconciliation of Indigenous infrastructure with non-Indigenous infrastructure;

- Reconciliation of Immemorial and section 35 (Aboriginal and Treaty) rights with non-Indigenous rights; and,

- Respectful partnerships.

These above objective-based criteria for Meaningful Consultation provide a platform through which the success of a specific Meaningful Consultation process can be measured. Functional criteria provide the working framework for the process. Functional criteria for Meaningful Consultation include that it:

- Is firmly founded in respect and sharing;

- Can accommodate the Immemorial and Aboriginal right to consultation;

- Is cultural in nature and able to accommodate the culture of different Indigenous Peoples;

- Can be adapted to provide consultation and accommodation for any Aboriginal right, Immemorial right or issue;

- Respects Indigenous law, Canadian law, and the United Nations definition of Meaningful Consultation;

- Can define and attain an appropriate depth for any needed Meaningful Consultation process.

- Is comprised of consultation and accommodation components;

- Can provide both Indigenous Nation and nation-to-nation components;

- Can identify and remove EFABs;

- Can identify and create legislation needed to accommodate Immemorial and Aboriginal rights;

- Can identify and create services through which new Indigenous and non-Indigenous roles can function;

- Has clear measures of success; and,

- Is transparent and accountable.

The Canadian federal government has rudimentary guidelines for Indigenous consultation17. These guidelines do not meet objective-based or functional criteria standards for Meaningful Consultation. This was evidenced with CIRNAC’s Indigenous engagement process on economic development18 and its engagement for drinking water and wastewater management19. These engagement processes did not meet criteria for Meaningful Consultation and they fell well short of Indigenous expectations for consultation of their rights to land and resource management. CIRNAC’s engagement processes also failed to respect Canada’s Rule of Law. Aboriginal and Immemorial rights fell victim to EFABs because one or both of the engagements broke Common Law when they:

- Used a public consultation process;20

- Failed to reconcile traditional Indigenous law and regulation on land and resource management with the sovereignty of the Crown;21

- Did not provide deep consultation on rights of high significance to Indigenous Peoples or when the risk of non-compensable damage was high;22

- Failed to consult Canada’s individual Indigenous Nations on matters affecting Indigenous land and resources;23

- Failed to provide a consultation process that recognized distinct features of the distinct Indigenous Peoples engaged in consultation;24

- Failed to recognize collective and communal Immemorial rights, Aboriginal rights and provide required community consultations;25

- Did not meet the Crown’s duty to consult when meetings occurred with Indigenous leaders in lieu of community and nation consultations;26 and,

- Provided legislation or regulations that make no attempt to accommodate constitutionally enshrined Aboriginal rights.2,3

Meaningful Consultation can not be defined for Indigenous Peoples, it must be defined by them. Each nation will have its own traditional law and customs to define the cultural nature and measures of success for Meaningful Consultation. We know enough to understand what Indigenous Peoples expect from Meaningful Consultation. However, the starting place for a complete Indigenous law definition of Meaningful Consultation in all Indigenous Nations is with Elders.

The Royal Commission on Indigenous Peoples spoke to many Indigenous leaders and Elders through an extensive, recorded process. From that testimony, Commissioners were clearly shown the role of Elders as national guides and keepers of traditional knowledge27. They carry oral traditional law for the nation and have a lead role in re-establishing culturally appropriate frameworks for infrastructure. Meaningful Consultation on any and all Immemorial rights, Aboriginal rights and issues starts in every Indigenous Nation with Elders.

The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples’ recommendation 4.3.1 states:

“Aboriginal, federal, provincial and territorial governments acknowledge the essential role of Elders and the traditional knowledge that they have to contribute in rebuilding Aboriginal nations and reconstructing institutions to support Aboriginal self-determination and well-being. This acknowledgement should be expressed in practice by:

- Involving Elders in conceptualizing, planning and monitoring nation-building activities and institutional development;

- Ensuring that the knowledge of both male and female Elders, as appropriate, is engaged in such activities;

- Compensating Elders in a manner that conforms to cultural practices and recognizes their expertise and contribution;

- Supporting gatherings and networks of Elders to share knowledge and experience with each other and to explore applications of traditional knowledge to contemporary issues; and

- Modifying regulations in non-Indigenous institutions that have the effect of excluding the participation of Elders on the basis of age.”28

The commission concluded that Indigenous Elders, First Nation, Métis and Inuit, are the source and teachers of the North American intellectual tradition29.

The Canadian federal government’s guidelines for Indigenous consultation17 do not meet the standards set out in the Report of the Royal commission on Aboriginal Peoples for inclusion of Indigenous Elders.

The Crown sees Meaningful Consultation very differently from the way Indigenous Peoples see Meaningful Consultation. Meaningful Consultation has been defined by the courts for it what is referred to as common law, a body of court decisions.

The Crown has a duty to consult Indigenous Peoples11 that arose from the recognition of its fiduciary duty toward Indigenous Peoples10. The Crown also has a more general duty to consult Indigenous Peoples arising out of the honour of the Crown13,14,15. The Crown’s duty to provide Meaningful Consultation to Indigenous Peoples applies to both federal and provincial governments30. The Crown’s duty to meaningfully consult is triggered when the Crown has knowledge of an Aboriginal right or title and considers an action that might adversely affect it31. The major difference between the fiduciary duty and the honour of the Crown is that the honour of the Crown,

“... can be triggered even where the Aboriginal interest is insufficiently specific to require that the Crown act in the Aboriginal group’s best interest (that is, as a fiduciary). In sum, where an Aboriginal group has no fiduciary protection, the honour of the Crown fills in to insure the Crown fulfills the section 35 goal of reconciliation of “the preexistence of Aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.”32

The nature of Meaningful Consultation is:

- It can not occur if the Crown unilaterally exploits the resource under consultation;33 and,

- It includes both the duty to consult and the duty to accommodate Indigenous Peoples.34

The nature of the duty to consult will vary with circumstances23,35 and includes:

- Deep consultation when the Aboriginal right and the potential infringement on the right is of high significance to Indigenous Peoples; or, the risk of non-compensable damage is high;22

- The full consent of an Indigenous Nation in some cases, particularly with hunting and fishing regulations;23

- A process which recognizes distinct features of the Indigenous Peoples engaged in consultation;24

- Consultation on issues involving Aboriginal and Treaty rights;10

- The right to be consulted on matters affecting wildlife conservation and natural resource management;21

- The right to be consulted on matters affecting hunting and fishing rights23,35

- Indigenous Elders as the oral repository for historical knowledge of culture, pre-contact practices, and for the values and morals of their culture to be used in consultation to define Aboriginal rights for pre-contact practices36

- Both community and nation consultations for Aboriginal rights that are collective or communal;25

- Aboriginal rights to hunt and fish as collective rights;37

- Meetings with Indigenous leaders do not meet the Crown’s duty to consult in situations of high significance;26

- The duty to consult cannot be met by giving Indigenous Peoples a short period of time to respond;38

- The duty to consult cannot be fulfilled by giving a general internet notice to the public inviting comments;38

- A public consultation process cannot meet the Crown’s duty to consult;20

- The Crown is obliged to establish a reasonable consultation process to meet its duty to consult;39

- A Memorandum of Understanding can be used to define a Meaningful Consultation framework40 but is not itself consultation; and,

- The Crown cannot meet its duty to consult Indigenous Peoples when it fails to follow its own process for consultation as set out in its policy for consultation with Indigenous Peoples.41

The duty to accommodate:

- First begins when the honour of the Crown demands recognition and accommodation of the distinct feature(s) in Indigenous society that need to be respected in the consultation process;42 and,

- Ends when the Crown’s effort to fulfill its duty to meaningful Indigenous consultation is assessed and found to be adequate by the overall offer of accommodation weighed against the potential impact of the infringement on the Aboriginal right under consultation.43

The nature of the duty to accommodate includes:

- The Crown is not negotiating in good faith and a willingness to accommodate Indigenous interests when the Crown does not make reasonable concessions;44

- The provision of technical assistance and funding to carry out the consultation when necessary;45

- Accommodation before final resolution to avoid irreparable harm to the Indigenous claim and in situations of high significance to Indigenous Peoples;46

- An amendment to Crown policy or practice to reconcile the Aboriginal right under consultation with the sovereignty of the Crown in situations of high significance to Indigenous Peoples;47

- Crown legislation and regulations are unreasonable when they make no attempt to accommodate the constitutionally enshrined rights of Indigenous Peoples2,3; and,

- The negotiation of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) does not provide accommodation of the Indigenous claim under consultation when conditions negotiated in the MOU process are not realized.48

The Canadian federal government’s guidelines for Indigenous consultation17 do not meet the standards set out in the above Rule of Law defined by Common Law. Further, the above common law definition still does not include Indigenous and international definitions of Meaningful Consultation.

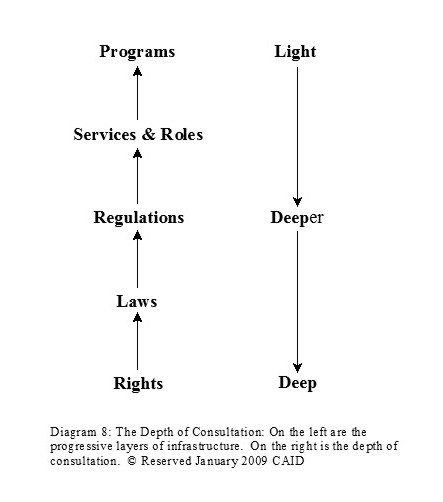

Canadian Common Law and United Nations recommendations define a variation to the depth of the Meaningful Consultation process depending on the significance of the issue under consultation. The functional definition to this depth of consultation can be found in the framework of infrastructure.

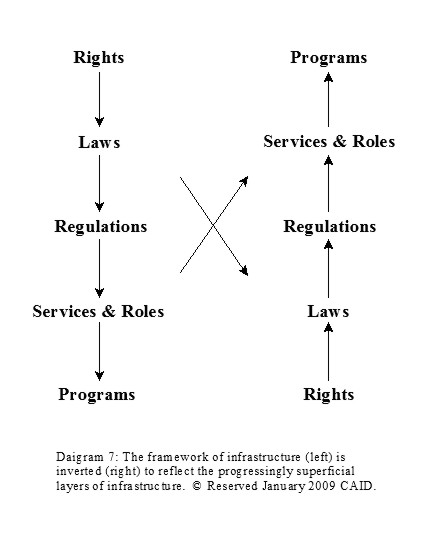

Meaningful consultation literally takes rights and reconciles them with rights, laws with laws, regulations with regulations, services with services and roles with roles (Diagram 6) until programs produced by the infrastructure are reconciled. If one takes the framework of infrastructure and inverts it to reflect the adding on of infrastructure layers, one can see that rights are a deeper layer then laws, which are deeper then regulations on so on up the line. When finished, programs are the most superficial and rights the deepest part of the framework of infrastructure (Diagram 7).

The inverted layers of the framework of infrastructure more adequately reflect the ease of accessibility one has to layers within national infrastructure. Programs are the most accessible and therefore the lightest depth of consultation. In fact, since programs are not infrastructure but tools of infrastructure, by nature they require very little formal consultation when all parties act in good faith. As one can see in diagram 8, the deepest depth of consultation is consultation on rights. Canada has done very little work with the reconciliation of Immemorial and Aboriginal rights. Because of this, every Meaningful Consultation will need to start at the deepest level for the Immemorial or Aboriginal right under consultation.

Four-Step Process of Meaningful Consultation:

The Crown is under a fiduciary obligation to reverse the colonial imbalance in its relationship with Indigenous Peoples and restore its relationship to a true partnership.1 The imbalance finds its root at the level of Indigenous versus non-Indigenous rights and its origin in Canada’s policy of assimilation. The process of Meaningful Consultation is the protocol to resolve this imbalance of rights in Canada.

Common Law (court decisions) in Canada has divided Meaningful Consultation into two components:

- Consultation; and,

- Accommodation.

These two steps might suffice in a different scenario but not for the Meaningful Consultation of pre-existing Indigenous rights in Canada. In Meaningful Consultation, Indigenous rights expressed in an Indigenous framework of infrastructure must reconcile with non-Indigenous rights expressed in the Canadian framework of infrastructure. The problem is two-fold:

- The policy of forced assimilation all but destroyed the Indigenous framework of infrastructure confounding consultation; and,

- Embedded forced assimilation barriers (EFABs) are present throughout the Canadian framework of infrastructure preventing the accommodation of the Indigenous framework.

To overcome this dysfunctional state, each of the two components in Meaningful Consultation must themselves be separated into two parts.51 The resulting four steps of Meaningful Consultation are:

- Nation Consultation;

- Nation-to-Nation Consultation;

- Harmonization; and,

- Restoration.

This four-step Meaningful Consultation process fulfills all consultation and accommodation requirements in Indigenous law, non-Indigenous common law, and recommendations made by the United Nations.

1. (Intra)Nation Consultation:

The Nation Consultation step is a consultation within an Indigenous Nation and is defined by Elders.49 The need for a Nation Consultation step is a direct consequence of the destruction of culture-based Indigenous infrastructures by the policy of forced assimilation. It has two functionally separate consultations:

- Elder Seeking: Consultation of Elders for definition of the cultural process for Nation Consultation. The cultural process would become the culturally-sensitive procedure used for the consultation of the Indigenous Nation. The Elder-defined consultation process will need to be ratified by the national governance. The cultural process will vary for different nations and may vary within each nation depending on the right under consultation.

- National Consultation: Consultation of the Indigenous Nation or urban population on a specific right using the Elder-defined consultation procedure. The Nation Consultation will have several components at different levels of the Indigenous Nation or urban population starting with Elders. The cultural database for the Indigenous right under consultation and the definition for cultural laws, regulations and services will be obtained from this component. The final results of the national consultation will need to be ratified by the national governance.

There are three basic goals to Nation Consultation.

- To obtain a definition for the culturally-sensitive procedure for the national consultation component of the Nation Consultation;

- To define the framework of infrastructure (law, regulation and services) for an Indigenous right: This framework can then be used in the reconciliation of Indigenous rights with non-Indigenous rights; and,

- To acquire a database on Indigenous culture: This database can then be drawn on by non-Indigenous institutions as a base to their understanding and respect of Indigenous culture, law, regulations, and rights.

Indigenous groups involved in the Nation Consultation.

- Elders;

- Communities; and,

- Councils;.

Needs of the Nation Consultation.

- Unconditional funding; and,

- Unencumbered expert technical support.

Given the magnitude of data acquisition and processing, plus the number of Indigenous Nation consultations that need to be undertaken across the country, a consultation infrastructure will be put in place using a non-governmental organization (NGO).

The Nation Consultation is a pre-requisite step to all aspects of the Meaningful Consultation process. However, it is simply a facilitated process to acquire a detailed database on Indigenous culture. Because of this, it is the only part of the four-step process that can be separated and initiated on its own without triggering a full Meaningful Consultation process with an Indigenous Nation.

2. Nation-to-Nation Consultation:

The Nation-to-Nation Consultation step can only occur after the Nation Consultation has finished. As its name suggests, it is a dialogue between the Indigenous Nation and the Crown. The Nation-to-Nation Consultation step produces defined parameters that need accommodation and has two distinct steps:

- Initiation: The national governing council of the Indigenous Nation is contacted by the Crown agency requesting consultation. The council in turn seeks guidance from Elders and the nation’s infrastructure framework concerning the necessary procedure and depth for the consultation.

- Consultation: Political leaders of the Indigenous Nation, with technical support from their infrastructure framework and the results of a Nation Consultation (see earlier), define what:

- Indigenous laws, regulations, services or roles must be respected in the right under consultation;

- Roles and partnerships the Indigenous Nation will have in the devolution of services for the right under consultation; and,

- Aspect of the right under consultation the Indigenous Nation will own, share or be compensated for.

The goal of Nation-to-Nation Consultation is to produce three lists that can be used to accommodate the Indigenous Nation, and right, under consultation. These lists are the:

- Infrastructure List: This list will contain the Indigenous Nation’s laws, regulations, services and roles that are affected by the issue under consultation. This list will be used in the accommodation component’s Harmonization step;

- Roles list: This list will contain the role(s) the Indigenous Nation will have in services within the reconciled infrastructure for the issue under consultation. This list will be used to define respectful partnerships between the Indigenous Nation and the consulting government in the accommodation component’s Restoration step;

- Programs List: This list will contain the part(s) of the reconciled infrastructure and its dividends the Indigenous Nation will have built within their nation. This list defines the destroyed culture-based Indigenous infrastructure that will be rebuilt in the accommodation component’s Restoration step. It also provides the Indigenous Nation’s Impact and Benefit Assessment for issues requiring compensation to the nation.

The Nation-to-Nation Consultation will need:

- A dedicated office within the consulting government;

- A pre-requisite Nation Consultation to provide guidance and define missing parts for the culture-based Indigenous infrastructure framework;

- Unencumbered technical support since most Indigenous Nations’ current infrastructures do not have the level of technical expertise required to support the decision making process of the nation’s political leaders; and,

- Unconditional Funding.

Given the number of Nation-to-Nation Consultations that must occur and the overt lack of professional technical expertise currently available within Indigenous Nations, a technical expertise infrastructure will be put in place using an NGO unfettered by conflict of interest to facilitate Indigenous leaders.

Negotiations are not part of the Meaningful Consultation process since in truly meaningful consultation both Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights have equal weight. However, equal-weighted, bilateral compromise may be needed to reconcile some of the items on the three lists. If so, that discussion and agreement to compromise would occur at this level by adding a third “Arbitration” step to the Nation-to-Nation Consultation based on infrastructure, roles and programs lists.

The need for a Harmonization step arises from the 1867 exclusion of Indigenous rights from the Constitution Act. The goal of Harmonization is the removal of embedded forced assimilation barriers (EFABs)5 that prevent the expression of Indigenous rights. The infrastructure list produced in the Nation-to-Nation Consultation is used in the Harmonization step. Any, and all, legislation, regulation, services or roles in non-Indigenous infrastructure that prevent the expression of Indigenous laws, regulations, services or roles found on the infrastructure list are identified and removed.

The Harmonization step needs unconditional government funding and is performed with two groups:

- The consulting federal, provincial or territorial government. One dedicated government office should be responsible for screening legislation and regulation to identify EFABs. The same office should oversee EFAB removal but individual departments, ministries and agencies should be responsible for removing EFABs found in their respective jurisdictions. and,

- One or more national Indigenous organizations (NIOs): These groups will provide legal and technical support to ensure transparency and consistency. These groups include the Assembly of First Nations, Congress of Indigenous Peoples, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Métis National Council. Other national Indigenous organizations (eg. Native Woman’s Association of Canada) have roles working in a special advisory capacity through these primary NIOs. All NIOs are subject to mandate from their Indigenous Nation and urban population grass-roots.

The goal of the Restoration step is the reconciliation of the Indigenous right under consultation to the sovereignty of the Crown. Restoration has two steps:

- Legislative: The roles list acquired in the Nation-to-Nation Consultation is realized through the introduction and enactment of legislation by the consulting government. Indigenous roles are created within reconciled infrastructure services and function in partnership with non-Indigenous roles.

- Operative: The programs list formulated in the Nation-to-Nation Consultation is used to build the Indigenous component of the reconciled infrastructure. Indigenous roles are enabled by establishing the Indigenous infrastructure service and its related programs. This step may include Impact and Benefit Assessment compensation.

The Legislative step needs unconditional funding and is performed by the same two groups used in the Harmonization step.

- A dedicated government office, and,

- National Indigenous Organizations.

The Operative step needs unconditional government funding and is a coordinated effort between the:

- Dedicated government office; and,

- The Indigenous Nation under consultation.

Reconciliation will be achieved when the paper, legislative, step in Restoration becomes functional, operative45

The Meaningful Consultation process has distinct steps each with clear goals. Each goal’s attainment is a clear measure of success. Goals are:

- 1. Nation Consultation:

- To define the cultural process for Nation Consultation;

- To define the framework of infrastructure for an Indigenous right;

- To acquire a database on Indigenous culture.

- 2. Nation-to-Nation Consultation:

- To define the depth of consultation required;

- To identify Indigenous rights, laws, regulations, services and roles that need to be harmonized with non-Indigenous infrastructure;

- To identify role(s) the Indigenous Nation will have in services within reconciled infrastructure; and,

- To identify services and their programs that will be built to provide Indigenous components of reconciled infrastructure.

- 3. Harmonization:

- To remove EFABs in non-Indigenous legislation and regulation that prevent the expression of Indigenous infrastructure.

- 4. Restoration:

- To create legislation that facilitates partnered Indigenous roles; and,

- To create the Indigenous service and programs component of reconciled infrastructure.

Transparency and Accountability

Meaningful Consultation needs six groups to move forward:

- The consulting government;

- The Indigenous Nation;

- An NGO to facilitate the Nation Consultation and generate the Indigenous culture database in Meaningful Consultation step 1;

- An NGO for Indigenous Nation technical support in Meaningful Consultation step 2;

- A dedicated government office for Meaningful Consultation steps 2, 3 and 4; and

- National Indigenous Organizations (NIOs) for Meaningful Consultation steps 3 and 4.

Each consulting government will need a dedicated department, ministry or agency for Meaningful Consultation. That office will need a mandate to:

- Engage Indigenous Nations in Nation-to-Nation Consultation of behalf of the government;

- Screen existing and proposed legislation and regulation for EFABs;

- Coordinate legislative and regulatory cleansing of EFABs;

- Create new legislation for partnered Indigenous roles; and,

- Create reconciled services and programs for Indigenous Nations.

Common Law in Canada has identified the requirement of federal, provincial and territorial governments to provide technical assistance and funding to Indigenous Peoples during consultation45. The United Nations has also called for ways to provide Indigenous Peoples with access to technical and financial resources4 to effectively participate in consultation, including through NGOs50. In the Meaningful Consultation process presented here, NGOs are used to facilitate Indigenous Nations both to create a culture database, and, to provide professional technical support for Indigenous leaders and nations. NGOs are used since they:

- Are not guided or limited by EFABs in the quality of work they can do for Indigenous Nations;

- Can not profit from the results of their work;

- Are not controlled politically by Indigenous leaders or the consulting government;

- Will provide consistent professional facilitation and support to Indigenous Nations;

- Will provide consistent data collection and processing for Indigenous Nations;

- Can be transparent for both Indigenous Nations and consulting governments; and,

- Can be accountable to both Indigenous Nations and consulting governments.

NIOs are involved separately from non-partizan NGOs that facilitate the Nation and Nation-to-Nation consultation. These NIOs have the expertise, grass-root support and existing infrastructure to protect Indigenous interests during the accommodation steps of Harmonization and Restoration.

With a dedicated government office, unconditional government funding and the combination of non-partizan NGOs and NIOs, the Meaningful Consultation process will remain transparent and accountable.

The four step Meaningful Consultation process52 is capable of honouring Indigenous law, Canadian legislation, common law and international recommendations on meaningful Indigenous consultation.

Meaningful Consultation of Indigenous rights is about functionally including those rights in Canada’s national infrastructure framework. To do this Indigenous and non-Indigenous national infrastructures must weave together to create a mosaic of local, regional and central services that together function as Canada’s national infrastructure, respecting both Indigenous and non-Indigenous rights. Unfortunately, most Indigenous infrastructure was destroyed by Canada’s policy of forced assimilation making it impossible to start Meaningful Consultation on an equal nation-to-nation footing.

The consultation of Indigenous Elders and Indigenous Nations before commencing nation-to-nation consultation provides a database for the knowledge and understanding of Indigenous infrastructure needed by both Indigenous and consulting governments to generate working definitions for culture-based Indigenous infrastructure. This “pre-requisite” intra-nation consultation is referred to as the Nation Consultation and it is the first of the four steps in Meaningful Consultation.

The information obtained from the Nation Consultation not only provides guidance to Indigenous leaders and a definition of Indigenous infrastructure for Canada to respect, it also provides a cultural database through which all non-Indigenous institutions and citizens can understand and respect Indigenous culture, law and regulation, and rights. If Canada had not forced the assimilation of Indigenous Peoples, the Nation Consultation step would not be necessary.

The Nation Consultation is a pre-requisite step to all aspects of the Meaningful Consultation process. It is a facilitated process to acquire a detailed database on Indigenous culture. Nation Consultation is the only part of the four-step Meaningful Consultation process that can be separated and initiated on its own without triggering a full process based on the Indigenous right to consultation.

In 1996, the Report of the Royal Commission on Indigenous Peoples recommended Canada fund the creation of a database on Indigenous history and culture that reflected the diversity of Indigenous Nations in Canada.6 That database was never created.

The Nation Consultation step is a consultation defined and guided by Elders49. It will need to occur with urban and land-based Indigenous populations and nations. It has two distinct components:

A. Elder Seeking: Consultation of Elders for definition of the cultural process for Nation Consultation. The cultural process would become the culturally-sensitive procedure used for the consultation of the Indigenous Nation or urban population.

1. Land-Based: A request to consult Elders is presented to the nation’s governing council. The format for the seeking will be set by the governance council. The resultant Elder-defined consultation process will need to be ratified by the national governance. The cultural process will vary for different nations and may vary within each nation depending on the right under consultation.

2. Urban-Based: Urban-based communities can be defined using the influence radius of existing Indigenous community centres (eg. United Native Friendship Centres and Metis Community Centres), by regional divisions of national Indigenous organizations (Assembly of First Nations, Congress of Indigenous Peoples, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Métis National Council) or, a working combination of Indigenous community centres and national Indigenous organizations. A request will be made to the national, regional or local office or governance to consult Elders or the council/group that has been created to provide Elder-based guidance. The defined consultation process will need to be ratified by the office or governance to whom the request was initially made.

B. National Consultation: Consultation of the Indigenous Nation on a specific right using the Elder-defined consultation procedure. The Nation Consultation has several components starting with Elders. The final results of the national consultation will need to be ratified by the national governance. The following are very basic examples of national consultation for discussion purposes only.

1. Land-based:

a. Elder Consultation: Has two components;

i. Base: Elders speak on the right under consultation to provide definition, history and a deep cultural understanding of the right; and,

ii. Bridge: Elders respond to specific questions on the right under consultation which focusses answers to provide a bridge (link) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies; between cultural knowledge and existing community, regional and global infrastructure for the expression of the right.

b. Community Consultation: Results of the Elder consultation are presented in each community. Community comments and concerns will identify and define cultural community roles, citizen needs and, services and programs needed to express the right under consultation;

c. Special Council Consultation: Comments and concerns from special councils on results of the Elder consultation will identify cultural special council roles and target group-specific service and program needs based on the expression of the right under consultation (eg. Women’s and Youth Councils);

d. Regional Resource Council Consultation: Results of the Elder, community and special council consultations are presented to regional resource councils. Their comments and concerns on practical application of results from the Elder consultation will identify cultural regional resource council roles and needed infrastructure services to provide programs identified in community and special council consultations; and,

e. Governing Council Consultation: Results of the Elder, community, special council and regional resource council consultations are presented to the nation’s governing council. Comments and concerns will identify cultural governing council roles and legislative issues needed to realize the expression of the right under consultation.

2. Urban Based: The hierarchical structure of the urban-based consultation may be very different then presented in this example. The primary reason for this is the utilization of community centres under the jurisdiction of different national, provincial, territorial or regional Indigenous organizations which we will refer to collectively as the Indigenous Centre Under Consultation (ACUC). Where Elders, special councils and governing bodies are located within these ACUCs will dramatically influence the format of the national consultation.

a. Elder Consultation: Has the same two components as in the land-based national consultation;

i. Base: See earlier.

ii. Bridge: See earlier.

b. Community Consultation: The community will be defined using the influence radius of the local community centre of the ACUC through which the consultation is occurring. The result of the Elder consultation is presented. Community comments and concerns will identify and define cultural community roles, citizen needs and, services and programs needed to express the right under consultation;

c. Special Council Consultation: Comments and concerns from special councils associated with the ACUC on results obtained with the Elder consultation will identify cultural special council roles and target group-specific service and program needs based on the expression of the right under consultation (eg. Women’s and Youth Councils); and,

d. ACUC Consultation: Results of the Elder, community and special council consultations are presented to the ACUC. Comments and concerns will identify cultural ACUC roles and legislative issues needed to realize the expression of the right under consultation.

The first step in Meaningful Consultation, Nation Consultation, has clear goals. Goal attainment is a clear measure of success. The first goal in Nation Consultation is the successful completion of Elder seeking; or,

- To obtain a definition for the culturally-sensitive procedure for the national consultation component of the Nation Consultation .

The second, and primary, goal in Nation Consultation is the completion of the national consultation; or,

- To obtain a database on Indigenous culture.

The success of the database will be measured by its ability to:

- Be drawn on by institutions for research and as a base for non-Indigenous understanding and respect for Indigenous culture, tradition, customs and rights; and,

- Be researched to specifically identify:

- Indigenous citizens’ needs that can be met by the expression of Indigenous culture and rights;

- Frameworks of Indigenous societal infrastructure (authority, law, regulation and services) that will allow the expression of Indigenous culture and rights; and,

- Programs that will allow for Indigenous needs to be met through the expression of Indigenous culture and rights.

A Nation Consultation that meets the above goals and measures of success will be able to provide the database for the respect and reconciliation of Indigenous rights with non-Indigenous rights.

The Nation Consultation has five basic requirements:

1. Indigenous Nations to be consulted: Included are:

- Elders;

- Citizens;

- Communities;

- Urban Community Centres;

- Special Councils;

- ACUCs;

- Resource Councils; and,

- Governing Councils.

2. Dedicated technical support: Due to the magnitude of data acquisition and processing, the number of Nation Consultations that need to be undertaken across the country, and the need for consistent, accountable data collection, a consultation infrastructure must be put in place using a non-partizan, non-governmental organization (NGO) to facilitate Nation Consultations.

3. Data handling system for:

- Acquisition;

- Nation monitoring during acquisition;

- Security and Transportation;

- Processing; and,

- Public Access.

4. Public Education Institution: to receive, house, provide access to, and maintain the hard and electronic copies of the database upon completion. Copies are also given to the Indigenous Nation.

5. Funding: The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommends the federal government fund the creation of consultation-based database6; common law identified the requirement of federal, provincial and territorial governments to provide technical assistance and funding during Indigenous consultation45; and the United Nations called for ways to provide Indigenous Peoples with access to technical and financial resources to participate in consultation50. Costs will be incurred by the Indigenous nation and the NGO. Funding is needed for:

- Consultation;

- Database Creation; and

- Database Maintenance.

4. Transparency and Accountability

Video and audio recorded during the Nation Consultations will be:

- Monitored live by the Nation;

- Unaltered data will be polished, translated and transcribed to text for use in the database; and,

- The database and summary reports of the database will be ratified by the Indigenous Nation.

A dedicated non-partizan NGO will be used to provide technical expertise to create the cultural database. A non-partizan NGO is used since it:

- Will not be guided or limited in the quality of work it can do for Indigenous Nations by a hidden policy;

- Can not profit from the results of its work;

- Is not controlled politically by Indigenous leaders or the Canadian government;

- Will provide consistent professional facilitation and support to Indigenous Nations;

- Will provide consistent data collection and processing for Indigenous Nations;

- Can be transparent for both Indigenous Nations and the Canadian government; and,

- Can be accountable to both Indigenous Nations and the Canadian government.

The combination of live monitoring, polished but unaltered data, nation ratification and the use of a non-partizan NGO will keep the Nation Consultation transparent and accountable.

1. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 2: Restructuring the Relationship. Part One: Chapter 2, Treaties; 3.7 The Fiduciary Relationship: Restoring the Treaty Partnership. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP2.2.pdf

2. R. v. Goodon, [2008], M.B.P.C. 59, at para. 81. https://caid.ca/GooDec2009.pdf

3. R. v. Powley, [2003] 2 S.C.R. 207, 2003 S.C.C. 43, at para. 55. https://caid.ca/PowDec2003.pdf

4. (2007) Resolution 61/295. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://caid.ca/UNIndDec010208.pdf

5. (2008) Herbert, R.G. A Model for the Reconciliation of Canada with its Indigenous Peoples; Restoration of Missing Infrastructure Phase 1: Pilot Program Development. A Proposal in Response to the Federal Government of Canada’s Objective to Reconcile with Indigenous Peoples in Canada. https://caid.ca/ModelInf091608.pdf

6. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 1: Looking Forward Looking Back. Part Three: Building the Foundation of a Renewed Relationship. Appendix E Summary of Recommendation in Volume 1. Recommendations 1.7.1 and 1.7.2. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP1.E.pdf

7. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 FCA 20, at para. 82. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

8. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 2: Restructuring the Relationship. Part One: Introduction. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP2.1.pdf

9. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 1: Looking Forward Looking Back. Part Three: Building the Foundation of a Renewed Relationship. Chapter14, The Turning Point. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP1.14.pdf

10. R. v. Vanderpeet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507 at para. 31. https://caid.ca/VanDec1996.pdf

11. R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075. https://caid.ca/Sparrow020908.pdf

12. Guerin v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 335. https://caid.ca/GueDec1984.pdf

13. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, 2004 S.C.C. 73. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

14. Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 550, 2004 SCC 74. https://caid.ca/TakDec2004.pdf

15. Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), [2005] S.C.J. No. 71, 2005 S.C.C. 69. https://caid.ca/MikDec2005.pdf

16. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 1: Looking Forward Looking Back. Part Three: Building the Foundation of a Renewed Relationship. Chapter 16, The Principles of a Renewed Relationship. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP1.16.pdf

17. (2008) Canada Aboriginal Consultation and Accommodation: Interim Guideline for Federal Officials to Fulfil the Legal Duty to Consult. https://caid.ca/CanConPol021508.pdf

18. (2008) Toward a New Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development Discussion Guide. https://caid.ca/INACEng2008.pdf

19. (2009) Drinking Water and Wastewater in First Nation Communities. Discussion Paper: Engagement Sessions on the Development of a Proposed Legislative Framework for Drinking Water and Wastewater in First Nation Communities. https://caid.ca/WaterEng2009.pdf

20. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 F.C.A 20, at para. 115. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

21. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 F.C.A 20, at para. 82. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

22. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 44. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

23. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 40. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

24. Wii'litswx v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2008] B.C.S.C. 1139, at para. 247. https://caid.ca/WiilitswxDec2008.pdf

25. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, at para 115. https://caid.ca/DelDec1997.pdf

26. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 FCA 20, at para. 118. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

27. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 4: Perspectives and Realities. Chapter 3, Elders’ Perspectives. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP4.3.pdf

28. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 4: Perspectives and Realities. Appendix A: Summary of Recommendation Volume 4. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP4.APP.A.pdf

29. (1996) Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 4: Perspectives and Realities. Chapter 3, Elders’ Perspectives; 6. A Call to Action. Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. https://caid.ca/RRCAP4.3.pdf

30. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 59. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

31. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 35 and 38. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

32. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 F.C.A. 20, at para. 81. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

33. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 27. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

34. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 60, 61, 62 and 63. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

35. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, at para 168. https://caid.ca/DelDec1997.pdf

36. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, at para 84, 85, 86 and 87. https://caid.ca/DelDec1997.pdf

37. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, at para.134. https://caid.ca/DelDec1997.pdf

38. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 F.C.A. 20, at para. 116. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

39. Huu-Ay-Aht First Nation et al. v. The Minister of Forests et al., [2005] B.C.S.C. 697, at para. 123. https://caid.ca/HuuDec2005.pdf

40. Gitanyow First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 B.C.S.C. 1734, at para. 58. https://caid.ca/GitDec2004.pdf

41. Huu-Ay-Aht First Nation et al. v. The Minister of Forests et al., [2005] B.C.S.C. 697, at para. 123. https://caid.ca/HuuDec2005.pdf

42. ii'litswx v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2008] B.C.S.C. 1139, at para 7. https://caid.ca/WiilitswxDec2008.pdf

43. Gitanyow First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 B.C.S.C. 1734, at para. 63. https://caid.ca/GitDec2004.pdf

44. Gitanyow First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 B.C.S.C. 1734, at para. 50. https://caid.ca/GitDec2004.pdf

45. Dene Tha’ First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Environment), [2006] F.C. 1354, 2008 FCA 20, at para. 134. https://caid.ca/DeneThaDec2006.pdf

46. Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, at para 47. https://caid.ca/HaidaDec010208.pdf

47. Wii'litswx v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2008] B.C.S.C. 1139, at para 10. https://caid.ca/WiilitswxDec2008.pdf

48. Gitanyow First Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 BCSC 1734, at para. 62. https://caid.ca/GitDec2004.pdf

49. (2008) Herbert, R. G., A Model to Establish a New Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development in Canada: A Proposal in Response to the Federal Government of Canada Objective to Establish a New Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development in Canada. https://caid.ca/Model031108.pdf

50. (2009) United Nations Human Rights Council. Promotion and Protection of all Human Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Including the Right to Development. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People James Anaya. A/HRC/12/34, at para. 71. https://caid.ca/UNHRC2009.pdf

51. (2009) Herbert, R. G., Meaningful Consultation in Canada: The Alternative to Forced Aboriginal Assimilation, p34. https://caid.ca/MeaCon092409.pdf

52. (2009) Herbert, R. G., Working Papers on Meaningful Aboriginal Consultation: Overview. https://caid.ca/MeaConOve101609.pdf

© Christian Aboriginal Infrastructure Developments

Follow

Follow